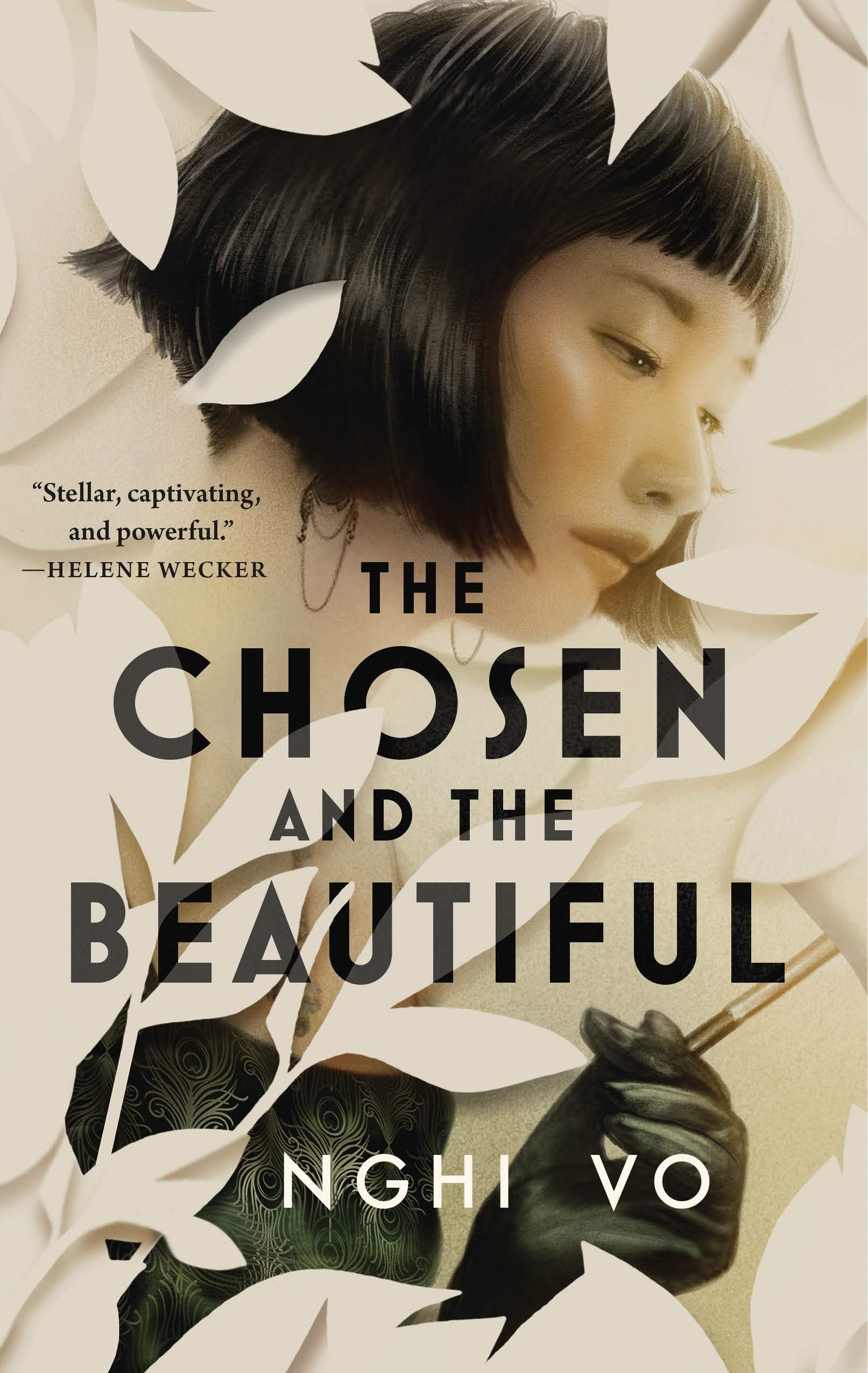

Review: The Chosen and the Beautiful by Nghi Vo

When I picked up Nghi Vo’s debut novel The Chosen and the Beautiful, I was excited to get a more femme retelling of one of my favorite books of all time, The Great Gatsby. What I ended up getting was a new mantra: if white men can rewrite history, women of color can rewrite their books.

Let’s face it, literature has stood the test of time better than history, anyway.

The Chosen and the Beautiful is told from the perspective of Nick Carraway’s main love interest, Jordan Baker. And Jordan is a queer, adopted Vietnamese woman who gets to see the best parts of society but doesn’t get to experience them due to her race. Oh, and she has magic powers. Of course, simply getting the story from Jordan’s POV wouldn’t be doing any justice to the people of color who were sitting on the fringes of the source material (oh Nick, you’re good and kind to your Finnish maid! Congrats!). It would not be delving into the difficulties and horrors women faced in an era when saying no to a man was an offense, but removing the unwanted baby he put in you was also unacceptable. It would be turning a blind eye to the theory that Nick is in love with Gatsby (and therefore refusing to pick a side between whether that’s gayification, or a valid possibility). It wouldn’t be throwing a bit of magic into the mix, since it goes so well with all the sinning that must be done in order to breathe new dimensions into The Great Gatsby. There has to be a taste of the hellish if the reader is to have fun incorporating people who were practically thought of as evil or magical in the ‘20s. The Chosen and the Beautiful is not cautionary and laid back the way The Great Gatsby is. It’s bold, fun, and sexy.

I mean, there are some really fun sex scenes, narrated in a very similar fashion to Gatsby itself. Everything I didn’t know I’d always needed.

Vo did an exquisite job not only catching and furthering the feel of The Great Gatsby but making it a little more upbeat, even when dealing with heavy topics. One must admit, whether they love or hate the original novel, that it can be dry and slow-moving. One could argue not a lot happens. And one could back that argument with the belief that it’s because of how easy straight, white men had it (and have it). Take, for example, the eyes of TJ Eckleburg. They’re one of the more ambiguous symbols in Gatsby: they symbolize something different to every character, though Wilson’s noting them as the judgemental eyes of God is the only solid interpretation we get. Jordan feels their weight whenever she goes through the Valley of Ashes and when she’s high off demon’s blood, which partygoers in Chosen drink for an extra kick, she destroys the billboard. She’s tired of being judged, being seen by the eyes of a man whose business failed yet his billboard remains.

The feminization of the characters’ interactions often happens “offscreen” in Gatsby, between Daisy and Jordan. While Nick is off worrying whether Gatsby likes him and trying to figure out the best responses to Tom’s bigotry, Jordan takes teenage Daisy to get a secret abortion so that she could keep growing into the perfect lady who would marry Tom. She uses magic papercutting skills to make a fake version of Daisy while she helps the real Daisy deal with being terribly drunk at the fact that she has to marry Tom. Women were dealing with the need to seem perfect so they could marry men they barely knew. Those men were bound to cheat, like Tom with Myrtle, and it was generally acknowledged, but the women having multiple partners, even when technically single, were frowned upon.

Outside of the goings-on and daily life of the characters, the historic backdrop is also important. In Gatsby, Nick has returned from war and isn’t too upset about it. And, of course, no one is legally allowed to drink so they do it illegally. These, again, are such male problems — one of them being a legitimate problem which wasn’t really touched on in Gatsby, the other…sort of just a pain in the butt.

Vo uses the ‘20s as an opportunity to really say something about race and racism at the time. In Chosen, a proclamation called The Manchester Act will be, and then is, passed. It removes Asian immigrants from America, and although Jordan was adopted by a white woman and has no true memory of growing up in Vietnam, she chooses to go. The party is over and she knows too much now, between meeting other Asian characters who also have her papercutting skills and have taught her about her past, to seeing just the kinds of people Nick, Daisy, Tom, and particularly Gatsby, are. She might not go “home”, but she can’t stay in America.

The death of Jay Gatsby is difficult, though Jordan had no true love for him anyway. The death of her relationship with American citizenship in ways beyond her control is a much truer ending. Though The Manchester Act is fictional, it is rooted in the true history of such acts as The Johnson-Reed act, which limited the number of immigrants who were allowed into America, and the Hart-Celler Act specifically targeted Mexican immigrants. It is a much bigger, scarier, history-altering problem than having to sneak a drink, or still have good money while everyone else is suffering through the Great Depression.

Jordan’s sex, sexuality, and ethnicity are a much more dramatic backdrop that’s greater than Gatsby’s source material.

In an effort to support Bookshop.org, this post contains affiliate links. We may receive a commission for purchases made through these links. Thank you for the support!